“The Fish and The Cat” is a parable for why bad explanations of reality are so reliable at generating blindspots and why this makes it hard to understand the functions that are the good explanations of reality.

To begin, let’s start in 2011. Physicist David Deutsch published a book called “The Beginning of Infinity1”. It is a very long and challenging book. Below is Naval Ravikant’s2 take on it.

I was pleasantly surprised a couple of years back when I opened an old book that I’d read a decade ago called The Beginning of Infinity by David Deutsch.

Sometimes you read a book and it makes a difference right away. Sometimes you read a book and you don’t understand it; then you read it at the right time and it makes a difference.

People throw around the phrase “mental models” a lot. Most mental models aren’t worth reading or thinking about or listening to because they’re trivial.

But the concepts that came out of The Beginning of Infinity are transformational because they very convincingly change the way that you look at what is true and what is not.

The important thing to understand is getting to what is true and what is not. Building from this context, we now layer in the idea of the Cargo Cult3, introduced by Nobel Prize Physicist Richard Feynman. This is a concept describing the perils of bad explanations and how we fool ourselves into believing how the bad explanation is the best way to understand reality.

I would like to call Cargo Cult Science. In the South Seas there is a Cargo Cult of people. During the war they saw airplanes land with lots of good materials, and they want the same thing to happen now. So they’ve arranged to make things like runways, to put fires along the sides of the runways, to make a wooden hut for a man to sit in, with two wooden pieces on his head like headphones and bars of bamboo sticking out like antennas—he’s the controller—and they wait for the airplanes to land. They’re doing everything right. The form is perfect. It looks exactly the way it looked before. But it doesn’t work. No airplanes land.

So I call these things Cargo Cult Science, because they follow all the apparent precepts and forms of scientific investigation, but they’re missing something essential, because the planes don’t land.” But this long history of learning how to not fool ourselves—of having utter scientific integrity—is, I’m sorry to say, something that we haven’t specifically included in any particular course that I know of. We just hope you’ve caught on by osmosis.

The first principle is that you must not fool yourself—and you are the easiest person to fool. So you have to be very careful about that. After you’ve not fooled yourself, it’s easy not to fool other scientists. You just have to be honest in a conventional way after that. One example of the principle is this: If you’ve made up your mind to test a theory, or you want to explain some idea, you should always decide to publish it whichever way it comes out. If we only publish results of a certain kind, we can make the argument look good.

We must publish both kinds of result. For example—let’s take advertising again—suppose some particular cigarette has some particular property, like low nicotine. It’s published widely by the company that this means it is good for you—they don’t say, for instance, that the tars are a different proportion, or that something else is the matter with the cigarette. In other words, publication probability depends upon the answer. That should not be done.

What we bring from here is that while X (less nicotine is good for you) may be true, if Y (more tar has a more severe impact on lifespan) is also true, than Z. (it is likely that it is less healthy for you in reality)

X is a dangerous and bad explanation. That makes it harder to get to Y and to understand Z.

Let’s simplify and reduce to “The Fish and The Cat”.

In Dr. Seuss’s book “the Cat in the Hat4”, there is a scene where the Fish tells the Cat why it is not a cat. The explanation of the Fish is that it has never heard of a six foot cat, (X) thus that the Cat is not a cat. This is a bad explanation. The truth is simple. If the cat has whiskers, a tail, a cat heart, a cat brain… it is empirically a cat. This is an infinitely better explanation. However, due to the bad explanation, the Fish fails to understand the reality.

Fish: “You are not a Cat. I’ve Never Heard of a Six foot Cat.”

Cat: “But I am a Cat. Technically I am a Cat in a Hat”

Fish: “You are not a Cat in a Hat. That’s not a Hat and you are not a Cat.”

Cat: “I am indeed a Cat. And this is indeed a Hat.”

It seems simple, but I find myself grappling with these types of blindspots5 all the time. Where there is a bad explanation that in and of itself stands in the way of the good explanation and requires a great deal of effort to get past.

Honorable mention!

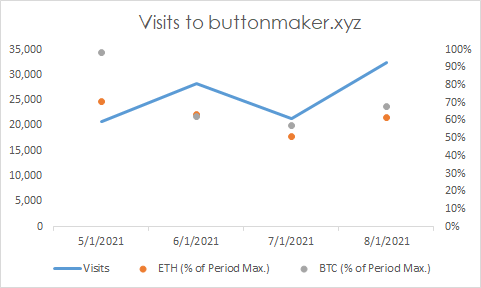

As we near the 20th anniversary of the iPod we look to an Internet form where 20 years ago intelligent people greatly underestimated the importance of the qualitative for the success of the pre-cursor to the most important invention6 of the 21st century.

Take a look at the explanations of why it would fail for yourself. https://forums.macrumors.com/threads/apples-new-thing-ipod.500/7

One bad explanation was that the competitors had more memory at a cheaper price. While this may be true (X), the better explanation (Y) on the impact of reality (Z) was that the product gave more value through the qualitative aspects of the user experience and user perception of the product. (underestimated factors from the forum commenters, in part because these are harder to quantify vs the reality of the mass market… also known as people and how they feel about the product)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Beginning_of_Infinity1

https://calteches.library.caltech.edu/51/2/CargoCult.htm 3

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Cat_in_the_Hat 4